Comune di Vilminore di Scalve (BG) Guide to the artistic and architectural heritage

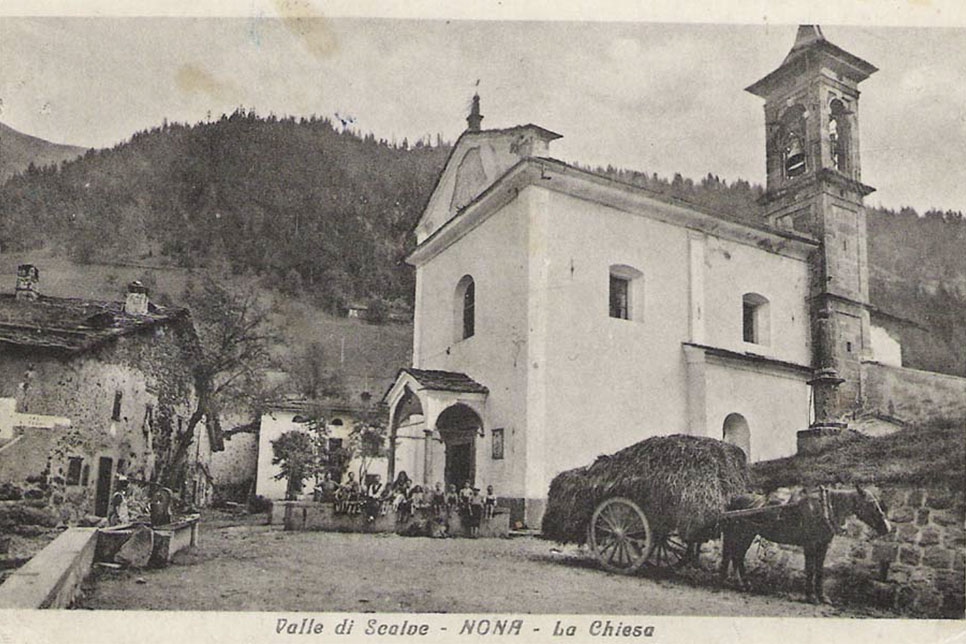

Frazione di Nona: Parish Church of SS. Rocco, Giacomo, Michele Arcangelo and Natività di Maria Vergine

History: The church of Nona, built at the end of the 16th century and consecrated as the parish church of Bishop Giovanni Emo on 15 July 1614, has a simple structure with a portico in late 16th-century style. The facade pronao has stone columns from the Dezzo. The portal is made of Scalve tuff and in the fastigium cartouche reads: "VIRGA JESSE FLORVIT MDCC" and on the architrave "ADORAB AD TEMPLUM/ SANCTUM TUUM". On the southern side, another pronao from the 20th century, designed by engineer G. Beretta. Inside, noteworthy are the wooden works by Giovanni Giuseppe Piccini (1661-1725), born in Nona and buried in this church.

Conservative events: In 1922 the decorative complex of the vault and presbytery was executed. In 1984 and 1991 important wooden works by Giovanni Giuseppe Piccini were stolen.

Cataloging: The information is taken from: Diocese of Bergamo, Catalog of Cultural Heritage - Parish of Pezzolo, 1997.

Bibliography:

G.S. PEDERSOLI - M. RICARDI, Guida di Val Camonica e valli confluenti, Gianico, Edizioni Toroselle, 1998, pp.893-895.

Guide created as part of the “Valorizzazione dei percorsi rurali” project by the Vilminore di Scalve 2003 - 2005 (project arch. A. Cristini) in collaboration with don F. Sonzogni, Parrocchia di Teveno.

Project co-financed by the European Union.

Documentation by G. Cavagnini e C. Coccoli.

The church of Nona in a postcard from the first decades of '900

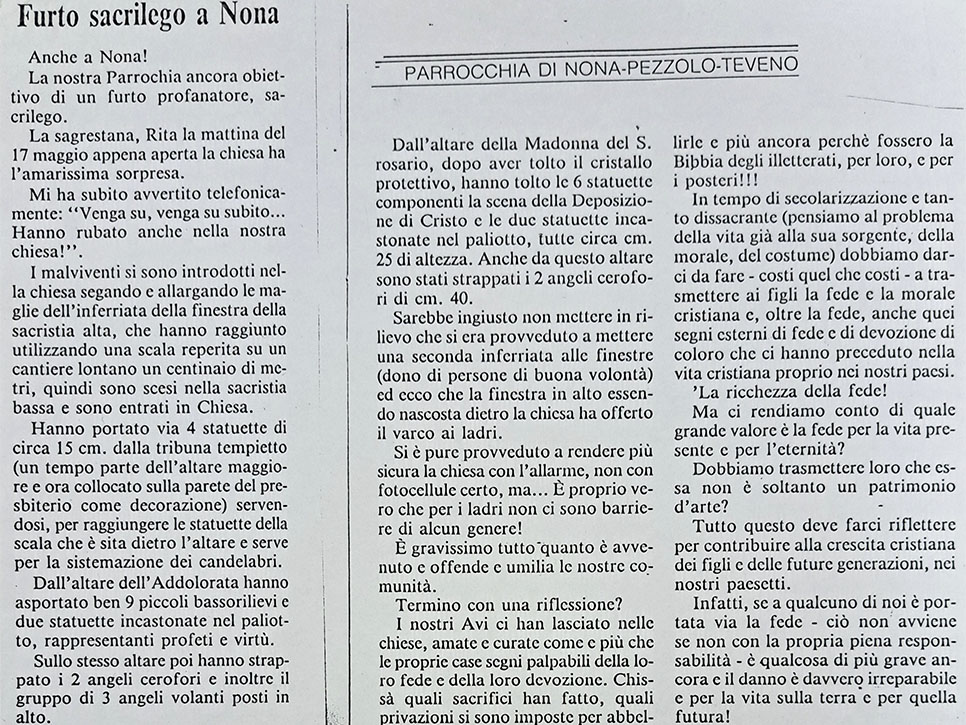

From “La voce della comunità della Valle di Scalve”,

April - May - June, 1991

From “L’Eco di Bergamo ” di Sabato 25 Maggio 1991,

local news section - province

On the occasion of the tercentenary of his death, in memory of the sad theft of some of his works, a temporary installation has been organized inside the church: several stylized elements have been placed where Piccini's works once stood, in those spaces whose significance today is measured by the emptiness that passes through them.

The aim is first and foremost to stimulate reflection on the value of works of art, their ability to impact our imagination and the construction of our worldview. And on what happens, conversely, when the artwork is removed from our gaze and its presence is reversed into absence. A second point of reflection concerns the profound connection between the work and the place for which the artist conceived it, and the fate of both—the work and its space—when this link is severed (Is it really severed? To what extent can it really be severed?). Finally, a space for reflection opens up on the way sculpture is today influenced and transformed by new design techniques: from the involvement of artificial intelligence in the design phases to 3D modeling and printing. Not only on how techniques have changed since, for example, Piccini's time, but on how these transformations can partially modify the very concept of artist, art and work of art.

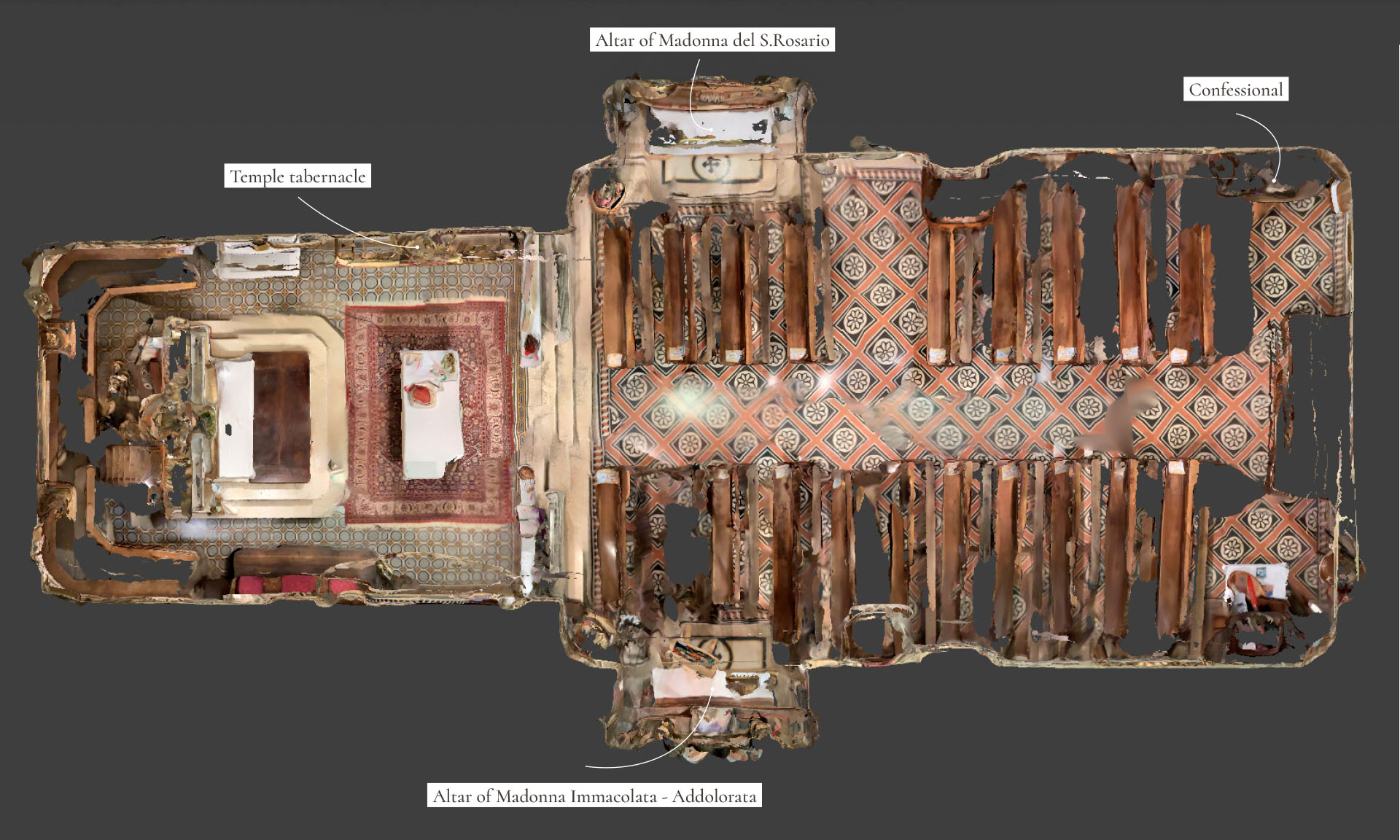

Internal plan of the church

Interior of the church - south side

Interior of the church - north side

A1

A2

A3

B1

B2

B3

B4

B5

C1

D1

D2

Over the past centuries, art, and sculpture in particular, have already undergone progressive transformations in execution techniques, thanks to the advent of new knowledge and new technologies. Similarly, but with a sudden acceleration whose effects we still struggle to measure, we are witnessing today a profound shift in the methods of conceiving and realizing artistic forms compared to the times when each work was the fruit of a labor entrusted almost entirely to the artist.

Two aspects in particular highlight this change:

In Piccini's time and until just a few years ago, the creation of a sculpture could only arise exclusively from the artist's mind (at most, guided by the client), then developed through sketches and drafts; finally, created by the artist's own hands through direct interaction with the material. Today, however, the conceptualization phase can be shared with artificial intelligence tools: the artist can generate forms and visual concepts through textual descriptions, leaving it up to the AI to propose new, original, and sometimes unpredictable solutions. In this way, the artist is no longer merely the author (or the sole author), but also the curator of a creative process shared with the machine, which can directly produce images and three-dimensional digital files ready for creation. This fact leads to a huge expansion of expressive possibilities, allowing even those without manual technical skills to engage in the artistic process. Here, then, are some of the questions that arise: how are the figure and role of the artist changing today? Where does its ability lie, at what point in the creative process? And is the creative dimension—assuming we can give it a univocal definition—still the exclusive domain of the artist (of man) or is it a faculty that can also be extended to the machine?

While in the 18th century (Piccini's century) every sculpture was made by hand, mostly from blocks of marble or wood, today it is possible to "print" a sculpture. 3D printers allow for the transformation of digital files, sometimes generated by AI, with extreme precision. Similarly, robots capable of sculpting even large-scale works with extreme precision have been developed in the same area of Massa Carrara, where Michelangelo carved marble. The use of new technologies undoubtedly allows for a reduction in production times. Even the physical effort required—the sculptor's arms, hands, and fingers—is no longer necessary. The margin for error itself, the scope for imperfection, approaches zero (but who establishes what is perfection or imperfection in a work of art? With respect to what criteria, from what time or culture?), while new avenues for formal experimentation and the use of non-traditional materials are opening up. Finally, the use of 3D printing makes sculpture more accessible on a production level, allowing for serial replicas or variations of a work without it having to be recreated from scratch each time by the artist's hands.